The Southern Paiute called this area a word that meant “the place where the rocks are sliding down all the time.” But why do we call it “Cedar Breaks”? Such an unusual name. The story is that early settlers (probably Mormons) mistook the juniper trees as cedars and described the steep, heavily eroded terrain that we’ll be seeing as breaks and so named the site as Cedar Breaks. Now we know the rest of the story.

But we have some learning to do before we get to the National Monument.

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established this area as a national monument to protect it for future generations (thank you!). This 3-mile wide amphitheater sets the stage for a breath-taking natural display. Limestone uplifted over millions of years and exposure by erosion has produced a cast of natural features that have been shaped by rain, ice, and wind. Oxidized iron and manganese in the stone produce the amphitheater’s red, yellow, and purple variations in color. (If you’d like to know more about how this all happened, go to the end of this post for the details.)

These views are especially vivid because they are concentrated in a small area surrounded by rich meadows and forest.

As we were entering the area, we met with fun father/son team who were taking some adventures while their mom and sister were at a camp together. Love meeting new people!

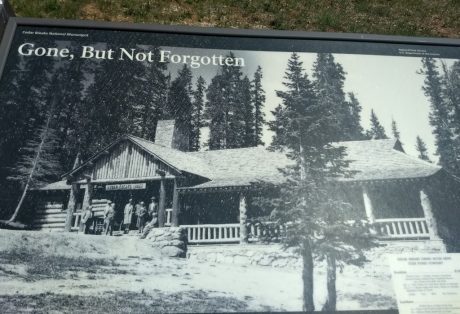

Then we came upon a sign on the side of the road that intrigued us.

Before Cedar Breaks became a national monument, this lodge was one stop on a tour of southern Utah parks sponsored by the Union Pacific Railroad.

Now onto this beautiful “amphitheater” at the main location of the park.

Also at this location was this original building that just looked like “a national park” to us.

This building is now the Visitor Center with its own history. Built in 1937 by the CCC, they used local spruce timber and volcanic rock as their materials. Those CCC guys did so much for us as a nation. Wish I had known some.

As we drove around the park, we stopped at the North View Overlook.

Ah, the vistas.

Ah, the wind.

Then we came to a third overlook.

view to the left

view to the right

Not all of the park is the deep canyon; it also has beautiful meadows and tall trees.

And it has an 11,000 summit called Brian Head. In the winter the park is open for cross-country skiing and snowshoeing. Snowmobiling is allowed on marked, groomed trails for those of you looking for a new place for winter sports (see the next post for more information and winter and summer sports opportunities).

We drove up to this summit and loved the view from this perspective.

wildflowers

Also in the park are lovely wildflowers. Over 300 species of wildflowers are in the park. Since it’s a protected area, many species are able to flourish. Here are just a few.

These are actually young pine cones.

We had wondered if the area had been a result of volcanoes. Here we found our answer. The view that we’re looking at is on the next picture.

These lava flows (below right side of picture) are only about 1000 – 5000 years old and come from vents and not a central volcano.

After all this driving around, we were getting hungry and needed lunch. We found a spot called Brian Head Grill so put it into our GPS. What a neat location we found that’s in the next post.

If you’d like more information on how Cedar Breaks was formed, here you go. Otherwise, go on to the next post.

history and geography

Since geography (like any other science) isn’t my cup of tea, I have a lot to learn. You too? Well we’ve learned that horizontal lines on mountains mean that once water covered the area and these lines are the marks that the water left. If vertical lines, they sideways pressure affected the mountains. But how did the mountains get to be so tall if they were once at water level, and where did the water go?

Here’s one description of how the area was formed. Shaped like a coliseum, the Amphitheater is 2500 feet deep and more than 3 miles across.

To the west of Cedar Breaks is Hurricane Fault. Starting 10 million years ago, dramatic movements caused a massive block of the Earth’s crust to drop to the west, forming the level valley far below. It also raised the Markagunt Plateau (where we’re standing) to its present altitude of 10,350 feet and exposed the edge of the formation to the elements.

A second description of how this area was formed.