As the emigrants in the west were getting settled into their new homes and jobs, they wanted to stay in touch with family and friends back home. Instead of waiting months for letters to go back and forth, they wanted (demanded?) faster service. The Pony Express was about ready to come on the scene.

In 1855 Congress appropriated $30,000 to see if camels could carry mail from Texas to California; this proved impractical.

John Butterfield won a $600,000 contract in 1857 that required mail delivery within 25 days. His overland stagecoach service began in 1858 on a 2800-mile route that left Fort Smith, Arkansas, went through El Paso, Texas, and Yuma in the Arizona Territory to end up in San Francisco. Despite its length and lack of water on the route, his stagecoaches didn’t have to navigate snowbound mountains.

With civil war threatening to close southern routes, the powerful southern political interests keeping government subsidies on these routes began to fade as northern politicians sought a central route. The idea of using a horse relay began to pick up steam.

Since William H. Russell and his freighting firm already had experience hauling cargo and passengers, were interested in picking up government mail contracts since they already provided mail and stagecoach service between the Missouri River and Salt Lake City. With some backing of partners and an interested senator, Russell committed his company to opening the express mail service on the central route in April 1860, the Pony Express Trail and the Central Overland Route. The company had 67 days to hire riders, station keepers, and mail handlers, as well as buy horses, food, and other supplies and distribute them to stations across the route (some were not yet built or even located).

Another partner, Alexander Majors, organized the route into 5 divisions:

1 – St. Joseph, Missouri, to Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory on the Platte River.

2 – Fort Kearny to Horseshoe Station near Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory. These two sections traced the route of the Oregon and California trails with a dip into Colorado at Julesburg.

3 – Fort Laramie to Fort Bridger and the Salt Lake Valley in Utah along the emigrant trail.

4 – Fort Bridger crossing the Great Basin following a route opened in 1858 by James Simpson that ran south of the Great Salt Lake desert to Roberts Creek Station north of today’s Eureka, Nevada.

5 – Roberts Creek Station to Sacramento (and sometimes San Francisco), the toughest part of the trip because it crossed the Nevada desert and rugged Sierra Nevada mountains.

Home stations were set up every 75 – 100 miles and smaller relay stations every 10 – 15 miles to provide riders with fresh horses as they rode to the next home station. Some stations were new, but others were upgraded from existing stagecoach stations. The number of stations went from 86 when the riders first started to 147 stations by mid-1861.

Riders were usually teenagers, and the average age was 20. Some riders were as young as 12 and were about the size of this young man on a train ride going out to a made-up Pony Express station with a rider for us to see.

the saddlebags that they used to carry mail.

Riders had to weigh less than 120 pounds, roughly the same size as a modern horse racing jockey, and carry 20 pounds of mail and 25 pounds of equipment. Weight slowed down the riders so was very important. Orphans were encouraged to apply since no one would miss them if they died.

The company employed between 80 and 100 riders and several hundred station workers. Riders earned wages of $100 – $150 a month, plus room and board. Good money for that day.

They had to take a loyalty oath that they’d stay away from bad language, alcohol, and quarrels or fights with other employees. They promised to be honest, faithful to duties, and act in all ways to bring confidence to their employers. Seems like the promise not to drink wasn’t followed at the relief stations.

While riders had to deal with weather, harsh terrain, and threats of attacks by bandits and Indians, life was probably worse for the stock keepers manning the relief stations. Their outposts were usually crude, dirt floor hovels equipped with little more than sleeping quarters and corrals for the horses. Few had roofs so they were open to sun, rain, and dust. Many were located in remote areas of the frontier, making them vulnerable to ambush.

Horses were selected for speed and endurance. The company bought 400 – 500 horses: thoroughbreds for eastern runs and California mustangs for western stretches. They averaged 10 miles an hour, at times galloping up to 25 miles per hour. During this route of 75 to 100 miles, a rider changed horses 8 to 10 times.

Mail traveled in 4 leather boxes (3 locked with mail and newspapers and 1 box unlocked for new mail) sewn onto the corners of a leather mochila (knapsack) that fit over the saddle. The design allowed for a fast removal and placement on a fresh horse.

Cost of mailing a letter was expensive: $5 for every half-ounce of mail ($130 today) reduced to $1 for every half-ounce. Everyday mail probably went by stagecoach, and the service was primarly used to deliver newspaper reports, government dispatches, and business documents, most of which were printed on tissue-thin paper to keep down costs because of the weight.

The exchange of horses and mail was more casual than legend and the movies have it. Riders often stopped to eat or drink and stretch their legs—unless the Indians were chasing them! We can “blame” Mark Twain for the legend of a fast exchange since he had written that the “transfer of rider and mailbag was made in the twinkling of an eye.”

The first ride was on April 3, 1860, from Sacramento. After nearly 2000 miles, the eastbound mail reached St. Joseph on April 13—10 days. From then on, one trip eastbound and one trip westbound happened every day. With the completion of the transcontinental telegraph on October 26, 1861, the Pony Express stopped being needed, and operations were closed down. The last run was on November 20, 1861. It completed some 300 runs each way—over 600,000 miles—and carried over 33,000 pieces of mail.

successes of the Pony Express

While the Pony Express only lasted 18 months, it achieved the goals of spreading news quickly and uniting the nation. By early 1861 war between the North and South seemed certain. Whether California remained in the Union depended on Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address. The Pony Express delivered Lincoln’s March 4 message to California in the fastest time ever—7 days and 17 hours—bringing news that helped the state loyal.

In April 1861, the Pony Express delivered word of the start of the Civil War. Until its last run, it brought news of battles and lists of dead and wounded to anxious westerners.

In such a short time, the Pony Express captured the hearts and imaginations of people around the world and marked a milestone in our nation’s communication system.

Today

Each year since 1978, the National Pony Express Association rides the trail in a 10-day, round-the-clock event. Over 500 riders follow a 1943-mile route that is as close as possible to the original trail. These riders use shortwave radios and cell phones to spread the news of their journey. This man, and the man on the horse shown previously, are part of this association and are proud of what they add to our history.

The biggest problem his riders have comes from the wild Mustangs. The stallions keep trying to entice the mares being ridden to come with them.

Much of this information was taken from the National Park Service’s brochure on the Pony Express National Historic Trail and some great websites. Thank you! We learned so much.

More information about the Pony Express is in our previous “Other Side” posts, especially around Genoa.

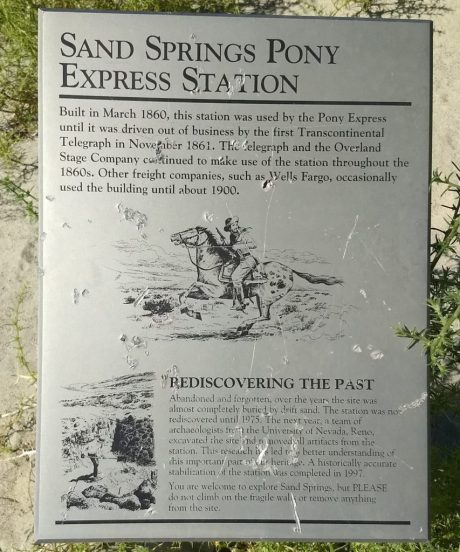

Sand Springs Station

Various remains of Pony Express stations are along Hwy. 50, but this one is probably the best one to see because drift sand almost completely covered it for many years. It was discovered in 1975, and the next year a team of archeologists form University of Nevada, Reno, excavated the site and removed artifacts from the station for further research. An historically accurate stabilization of the station was finished in 1997.

Here’s the design.

Signs from this area gave us additional information on the Pony Express. They were really hard to read so I’ll just summarize for you

Horses – As we’ve said, between 400 – 500 horses chosen for speed and endurance were used by the riders. They galloped over rocks, desert sands, and snow with little food and water. They bravely outran Indian attacks. Breeds like Morgans and Thoroughbreds were used in the east, Pintos in the middle of the ride, and Mustangs in the west.

Equipment – 2 Navy Colt revolvers, perhaps a rifle, a Bowie knife, horn to sound arrivals, Bible for courage, and the Mochila pouch for carrying the mail.

Exceptions – Of the 120 riders riding 650,000 miles, only once did the mail not make it because the horse and rider were killed. One schedule was not completed, and one time the mail was lost. Pretty good statistics I think.

The Pony Express really has captured our imagination as a symbol of man’s desire to improve on what is. The company lost money because of high operating costs, especially during the Pyramid Lake Wars in the summer of 1860 that cost the company around $75,000 because of the temporary shutdown. The owners may have been glad that the transcontinental telegraph took over communication between east and west when it did, but I’m certain that the owners were proud of what they accomplished for the nation.