A friend on FaceBook said that her favorite place along the Virginia coast was Jamestown. Hmmm. Since we’ve already decided to come back to Colonial Williamsburg in December to see the Christmas decorations, we decided to spend our 3rd day in Virginia exploring Jamestown, the first permanent British settlement in Virginia (not counting the lost colony). I wasn’t excited about coming here but am so glad we did!

This post will concentrate on the excavating that’s being done at the original site and what the archeologists have found and are finding. The next Jamestown post will give you more, behind-the-scenes information.

By the mid-1800s, people began to believe that any remains of the 1607 James Fort had been destroyed by erosion from the James River. By 1893, only the brick church tower remained above ground from original Jamestown. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities bought 22 1/2 acres of the land around the tower in hopes of finding a remnant of history.

The tower’s exact construction date is still debatable. What is known is that in 1617 Captain Samuel Argall (we’ll learn more about him later in this post) ordered a church to be built to replace the large timber-framed church where Pocahontas and John Rolfe were married in 1614. Argall’s church was the meeting place of the first representative legislative assembly in British North America in 1619. It was later replaced by a brick structure to reduce fire hazards and better serve an expanding colonial population. (info from historicJamestowne.org)

This drawing is how the fort would have looked based on what we know now and shows why the shoreline had to have the seawall built to stop further erosion.

The view of the James River from the fort.

Our first-year archeologist tour guide did a wonderful job of explaining all the work they were doing here at Jamestown. She told the facts like she was telling a story.

entering the site of 1607 James Fort

This site is the heart of the first, permanent English settlement in North America. What we’ll be seeing is about 1 acre in a triangular-shaped fortification.

In 1994, Dr. William Kelsey began the archaeological project to test his theory that the protected land around the church tower contained the archaeological remains of the fort that was thought to be lost.

Next to the tower and the church, archeologists have discovered more remains underground. Since the burial site in this picture is so close to the building, they believe that this must have been an important person. The staff is now building an enclosed area to protect the dig from winter’s harsh weather as they undercover what is buried below ground.

the barracks

Between the church tower and the river is this representation of the soldiers barracks that existed here from 1607 to 1624.

Most of the buildings that they’ve found here were of earthfast or post-in-ground construction. Structural posts were seated in the ground without the use of footings. Once the building disappeared, rotted posts and post-holes remained. Based on the patterns of these post-holes, these early structures were probably constructed in a style known as “Mud and Stud,” a common way of building found in the 17th-century document sources and in centuries-old buildings in Lincolnshire, U.K.

This barracks had a cellar, which was the first major archeological feature identified from the fort period. It became a trash pit once the building fell into disrepair. Many later 16th- and early 17th-century artifacts were found through careful excavation techniques.

A mud and stud building is a wood frame structure covered with mud plaster and roofed with thatch (example on the left in the picture).

artillery area to protect the fort

1608 church

Excavations have unearthed the remains of the first substantial Jamestown church built in 1608. The large post-in-ground building was identified by the spacing of several major structural posts matching the dimensions of the church recorded by Secretary of the Colony, William Strachey.

The chancel is where the communion table stood so would have been considered the holiest part of the building. The discovery and identification of the men buried here reveal new clues about the challenges faced by the colony and the importance of religion at Jamestown.

The 4 men buried here included the 1st Anglican minister at Jamestown who helped to quench dissent among the colony’s leaders, a knight and officer, a council member, and a military officer.

The layout of the 4 men buried in the chapel.

The posts are in the post-holes that the archeologists found and show the layout of the chapel.

A closeup of the area where the 4 men were buried.

A view from the other direction showing the location of the post-holes that mark the shape of the building.

model of the fort

The next 2 pictures are different views of a model of the James Fort. The church tower is a good way to get acclimated.

The numbers on the picture identify structures in the fort.

#2 are the first buildings: barracks, living quarters, and the fort’s “factory.”

The original buildings were made of forked trees set in the ground, mud-covered walls, and thatched roofs.

#4 are excavations of an unmarked burial ground near the west gate with more than 10 individual and double graves of men who died during the first summer of 1607.

#6 West of the fort in a military drill field was a brick-lined well filled with armor, tools, and early 17th-century trash.

#7 The church tower is included on this model as a reference point only since it post-dates James Fort.

Captain John Smith

If you would have asked me about Jamestown before we came here, I could have mentioned an early settlement, John Smith, and Pocahontas. You too?

What do you know about this man’s history? I don’t know anything either, so let’s learn about him together.

Born in 1580, John Smith was the son of a farmer of modest means. Going out on his own, he became a solder, fought in the Netherlands and in Hungary where he was captured, taken to Turkey, and sold into slavery in Russia. (Oh my.) He murdered his master, escaped, and found his way back to Hungary to collect a promised monetary reward and a coat-of-arms. He got back to England in time to participate in the settlement of Virginia.

Personality-wise, he was arrogant and boastful, often tactless, and sometimes brutal. He was physically strong and worldly wise, making an excellent settler—but his personality, obvious qualifications, and his low social position infuriated many of the colony’s leaders and settlers. Despite their feelings about him, he was named to the first Council in May 1607.

Smith learned the Indians’ language and became the colony’s principal Indian trader. During the summer of 1608, he led a 3000-mile expedition in an open boat to explore and map Chesapeake Bay and its principal rivers.

On September 10, 1608, the Council elected him Governor for a 1-year term. He was an able leader who understood both the Indians and the settlers’ needs, and the colony prospered under his leadership.

Captain Smith returned to England in October 1609 following an accidental gunpowder burn and became Virginia’s most effective proponent and historian. Once he left, the Indians felt free to harass the settlers; his presence had kept them away.

In 1614 he made a short voyage back to New England where he explored and mapped the coast from Cape Cod to Maine. Smith returned to England and never visited Virginia again, never married, and never received the recognition he thought he deserved. He died in 1631 and was buried in St. Sepulchre’s Church in London.

Pocahontas

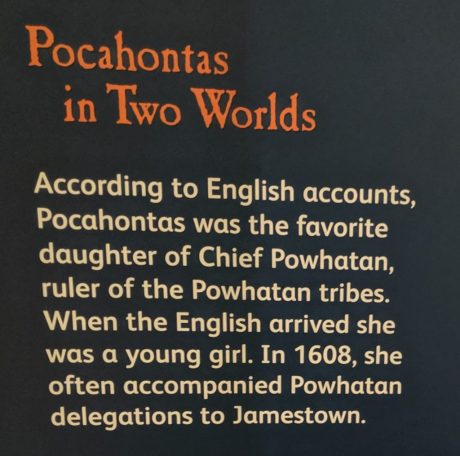

The favorite daughter of Chief Powhatan, ruler of the Powhatan tribes, Pocahontas was a young girl when the English arrived.

Around 1610, Pocahontas married a Powhatan Indian, but 3 years later she was kidnapped and held hostage by Captain Samuel Argall. While in captivity, she converted to Christianity, took the name Rebecca, and married colonist John Rolfe, a widow.

The Rolfes with their son Thomas and a contingent of Powhatan traveled to England in 1616 to build support for the Virginia Company. The next year Pocahontas became ill and died in England.

Pocahontas rescues John Smith?

John Smith being rescued by Pocahontas is one of Jamestown’s most famous stories, but is it true? In Smith’s account, Powhatan ordered his execution, and Pocahontas interceded and saved Smith’s life.

Critics say that Smith’s autobiographies tells of other times that sympathetic noblewomen came to the captain’s rescue. I think he was a good story teller.

uses of old wells

This well outside the west side of the fort was used during the first quarter of the 17th century in the early years of Jamestown. When no longer usable to draw water, wells were used as garbage bins.

Feel like you have a better understanding of Jamestown and its importance as the earliest colony in North America? Wait until the next post when you get the rest of the story!