Just like the land changed over thousands of years, once Native Americans and Europeans started discovering this land in northeastern North Dakota, life started changing for them. When we explore a state, we never know what we’re going to find ahead of time. What first intrigued me about this corner of North Dakota was the name of where we stayed: Icelandic State Park. If people from Iceland started coming here, what was the draw? The museum at the park’s headquarters started answering my questions.

We’ll be covering a number of topics in this post that span a number of years, but this isn’t the final word on any of these topics. We’ll add to what we learn here when we explore 2 other museums in the county, as well as elsewhere in the state.

beginnings of the native peoples

- Around 1100 A.D., people know as the Algonquin “Bison Path People,” later referred to as the Arapahoe-Atsina and the Mountain Crow, came into the Northern Valley and may have stayed until around 1700. Eventually they settled west of North Dakota.

- About 800 years ago, ancestors of some of present day Native Americans began moving into the area from the south, east, and north, including the Mandan, Arikara, Hidatsa, Ojibway, and Sioux. Their descendants still live in North Dakota.

When they camped, she did all the work to set up camp after relieving herself of her bundles and laying the baby on the ground.

When the lake dried up about 7000 years ago, the old lake bed became the Red River Valley. The western bank of this lake is known today as the Pembina Escarpment, which rises 300 to 500 feet above the old lake bed. West of Fargo (closer to the South Dakota border), the escarpment, or steep slope, is barely noticeable.

The Missouri River runs diagonally through the state, creating the Missouri Escarpment and the Missouri Plateau. We’ll learn more about how the Missouri River affected North Dakota as we travel west on our trip.

The old lake bed was covered with tall and medium grasses. The tall grasses, growing 4-6 feet tall, were dominant. On the Drift Prairie, the medium grasses became shorter as the plant life adapted to the more semi-arid climate. Eventually the entire region grew wheat and flax, the most important cash crops during the settlement period of 1870-1920.

fur trading changed everything

The first change to the peoples in this region was the fur trading with the furs that the Natives provided and that Europeans and eastern Americans desired. Three companies operated in this region.

- Hudson’s Bay Company – It was incorporated in England on May 2, 1670, for 3 reasons: seek a northwest passage to the Pacific, occupy the lands next to Hudson Bay, and carry on any commerce with those lands that might prove profitable. Its headquarters are now in Toronto.

- North West Company – It originally was a French company since the French had controlled much of what is now Canada in the early 1700s. It was founded after the British won control of Canada in 1763 to expand the French fur trade into the Canadian interior. From 1770 to 1821, it was headquartered in Montreal when it became part of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821.

- American Fur Company – It was founded in 1808 by John Jacob Astor to compete with Hudson’s Bay Company, capitalizing on anti-British sentiments and Astor’s commercial strategies to become one of the first trusts in American business to work with other companies to provide its product.

Beginning in the 1790s, a fur trading settlement was established at Pembina where the Red and Pembina Rivers merged. In 1801, a fur trading settlement was set up about 30 miles west of Pembina on the Pembina River known today as Walhalla.

Alexander Henry, an agent for the North West Company, ran other local fur posts. The Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, wanting to expand their territories from the east, were both British fur trading concerns, competing fiercely for the fur trade. These fur posts flourished in the Red River Valley until the late 1850s.

more about Alexander Henry

You never know when or where you’ll discover historical details. On our way south to Grand Forks close to the state’s border with Minnesota to see a podiatrist about my ankle, we stopped at this rest stop.

Outside was a display about Alexander Henry that we found really interesting.

With a group of 8 “north canoes” that were designed for river travel and manned by French-Canadian “voyagers,” he followed the regular fur trade route from Grand Portage to the Pigeon River, Rainy Lake, Lake of the Woods, Winnipeg River, Lake Winnipeg, and then up the Red River (see the next picture for this route). The journey required over 62 portages, some of which were 1000 yards long.

Henry built his post at this spot instead of further north on the Red River because he was afraid of the Sioux who roamed the area, calling it his Park River post since the Park River joined the Red River at this spot. He spent a winter here before moving north to Pembina where he built a permanent post. This post remained open until the fur trade died off in this area.

He and his men were credited with creating the Red River ox cart (which we see later in this post). The original cart had solid wooden wheels cut from the trunk of a tree. Henry’s most valuable contribution to the history of this area was his journals because he was a prolific writer who kept a record of his daily dealings around his trading post. These journals are an important link to our knowledge of frontier life.

back to fur trading

We’ll learn more about these fur trading posts as we travel west in the state.

farmers arrived

They wintered at Pembina and moved back to the Winnipeg area in the spring, moving back and forth for the next 3 years. Each spring a few remained at Pembina and in the Walhalla area to the west to become the first permanent white settlers in this area.

a new people

This next display stopped us in our tracks. We had never heard of this culture and still have trouble remembering how to pronounce their name: Metis (MAY tee).

The Metis trapped and traded at the posts and proudly declared themselves as free men since they didn’t work for a single fur company. Each year they went on an annual buffalo hunt, families and all, living in tepees around the herds for months at a time. St. Joseph (Walhalla) was still a thriving Metis community in 1856. Wanting their own land, the Manitoba Act passed in 1870 guaranteed rights and land titles that satisfied their demands, and they dropped their idea of a Metis nation.

left picture: Father Belcourt was the only early missionary preaching to both Indians and settlers.

right picture: Father Belcourt’s log missions at at Pembina

bottom picture: a Metis woman in a Red River ox cart around 1870

Red River ox carts

These ox carts were a staple for families during this period of growth.

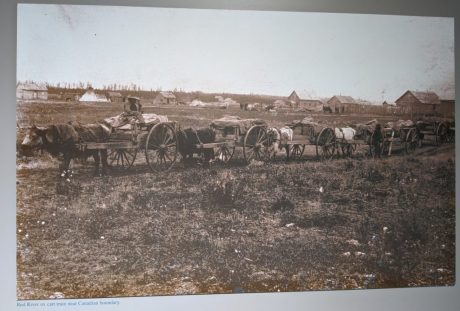

Ox carts transported furs along these trails and hauled food for trading back to the military forts and trading posts. Several Red River trails were used before 1870. The River Trail stretched along the west side of the river from Winnipeg to Fort Abercrombie in North Dakota. In the northern part of the region, an ox cart trail called the Ridge Trail ran along the Pembina Escarpment. It was used much more than the River Trail because the streams were easier to cross, the land was higher with fewer water holes, and the soil was sandy rather the gumbo near the river.

These ox cart trails were the only routes in and out of the area from 1820 until the 1860s.

right: Red River carts

bottom: an 1858 Red River cart encampment

We’ll learn more about these ox carts in future posts.

Now that we’ve spent time looking at the history of the area, let’s start looking at how the state changed as more and more Europeans and Americans from the East moved here.