The officers’ quarters building in the historic area of Fredericton houses the Fredericton Region Museum that gave us some great insights into the province. The end of the building that we see in this picture was the connection to the married officers building that burned down.

Early transportation by coach and boat was long and uncomfortable that led to multiple inns and hotels being built for the travelers’ comfort.

All inns shared similar themes: the lobby and dining rooms were much nicer than the sleeping quarters, often the men and women had separate entrances (don’t know why), and most inns had a stable so horses were ready for the next stage of the trip.

Two of the famous hotels were the Weverly Hotel and the Windsor Hotel.

Bottom: Windsor Hotel

As we started our museum self-guided tour, we saw this library cabinet from the Queen Hotel.

encyclopedias and novels for the guests to use.

At this point, I decided not to take pictures of every sign we see unless it was really important, so don’t worry, you’re safe.

a famous frog

The Coleman frog is famous in this area.

Here’s the frog’s background. In 1885, Fred Coleman built a summer hotel at Heron’s Lake, now Killarney Lake. He stocked it with fish and planted an orchard. One day while fishing, a large frog jumped into his boat. Legend tells us that Coleman befriended the frog and fed it whenever they met on the lake so that it grew to be enormous—42 pounds.

early NB history

Displays in the next rooms feature the Acadians (French fur trappers), the Aboriginals (natives), and Loyalists who came from the colonies. Then we’ll see the early political life of New Brunswick, the transformation of how medical care has been provided in the province, tools of the medical trade, and WWI and the Canadians.

Acadian settlement at Pointe Sainte-Anne and its destruction in February 1759

the wars between France and England.

France controlled much of New Brunswick area until the British started wanting control because of its “land” in the American colonies. The final contest for empire between Britain and France was fought out in the War of Succession (1744-1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). The first war proved inconclusive and the French then built 2 defensive forts. The British strategy then was to bring massive superiority to bear on each point in its defenses. In the spring of 1755, Britain sent 2000 colonial militia and 500 regulars to face the 200 French regulars, Acadian militia, and the Mi’kmaq (native tribe) at Fort Beausejour, one of the recently built defensive forts.

Since Britain lacked the power to govern the Acadians, in July 1755 Lt. Governor Lawrence ordered them to swear an oath of allegiance to the British crown. When they refused a second time, Lawrence concluded that they were deliberately opting for France and sent Lt. Colonel John Winslow to begin deporting them. About 1/3 fled into the unpopulated areas on the Northumberland shore, Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton, and the interior of Nova Scotia, while the rest were deported to southern Louisiana.

As the war turned in the British favor, the remaining Acadians were seen as a threat to be eliminated since they were military enemies, French and Catholic, allies of the Natives, and occupiers of rich land. The British assaults were vicious: they killed men, women, children, and livestock; burned houses, barns, and churches; and destroyed crops.

British supremacy was confirmed at the Treaty of Paris in 1763, which transferred all of New France and the rest of Acadia to Britain while the American colonies won its war against England.

treatment of native children

Since the natives had sided with the much-despised French, the British didn’t treat the native children very well. They created residential schools for these children for education but also to minimize and weaken family ties and cultural linkage and indoctrinate them in the British way of society. Sounds like what we did here in the U.S. too.

The children persevered through poor living conditions, overcrowding, lack of academic education, forced labor, hunger, and punishment for speaking their native language. One school was in New Brunswick from 1787 to 1826, and another in Nova Scotia that operated from 1930 to 1967. Since this second one was a later school, I’m sure the leaders had learned some good lessons from the earlier schools.

loyalists

Once the British settled their issue with the French at the end of the Seven Years War (actually it lasted 9 years), New Englanders, known as Planters, started moving north to claim land they thought they had conquered for Britain and for themselves. They were successful at farming, fishing, lumbering, and commerce; many of them were Congregationalists who later became Methodists and Baptists.

The outbreak of the American War of Independence raised the question of who the New Englanders would support. Merchants in Saint John were pro-British, but many other settlers were sympathetic to the rebellious [interesting term] colonies. The British navy soon gained complete control of the Bay of Fundy and the coast of Maine, ending any unrest or threat. Early American defeats and British bribes convinced the natives that neutrality was their best option, and so for the first time they weren’t an important factor in warfare.

Many of those living in American sympathize with the British, so when the British lost the war, many of the “Loyalists” became refugees. Some 15,000 of them came to the northwest side of the Bay of Fundy. While most were British, many were German, Dutch, or Irish, and several were Blacks. They came from all classes, trades, and professions. Most had no money or resources so needed land, housing, food, implements, and supplies so they could survive the first difficult years.

The British authorities hadn’t planned for this migration. The Loyalist officers assumed they would receive large grants of land, and senior officers assumed they would receive huge estates—with the workers to work their land because of the feudal structures in Europe they were used to. The majority of the Loyalist exodus however, consisted of farmers and workers, and they had no plans of working someone else’s estate. Besides, many of them had come from coastal areas so didn’t know how to live on the frontier and weren’t prepared for the harsher climate.

black Loyalists

Just as the officers and senior officers had their dreams shattered, the Blacks who came north had thought that their lives would dramatically improved because of their support of the British. Most were freeman, and slavery soon became illegal by 1830. But they were given poor land and discriminated against, and many soon left for the free colony of Sierra Leone in Africa.

much of this historic information is from “A Short History of New Brunswick” that we showed you in a previous post—thank you to the author, Dr. Ed Whitcomb

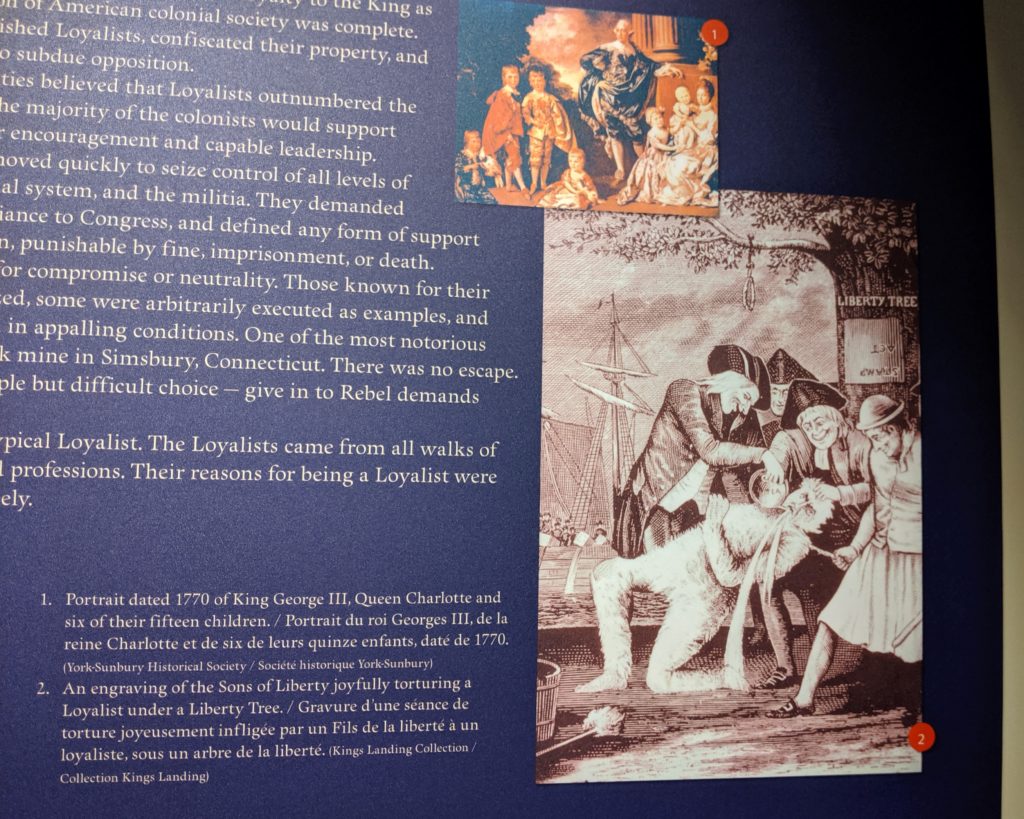

view of the “enemy”

What a different point of view for us: “When the Rebel-controlled Congress declared loyalty to the King as traitorous, the division of American colonial society was complete.”

Any form of support to the Crown was considered treason. The Loyalists could either give in to Rebel demands or flee. Sure enough, in 1773, the Simsbury Mine, 14 miles northwest of Hartford, Connecticut, was turned into a dungeon, a wretched prison named Newgate, after the famed jail in England. Newgate could hold more than 100 prisoners in its caverns at any one time. Of course they don’t mention the horrid British prison ships that held American war prisoners.

And we think that political cartoons and newspaper articles are bad now. Look at this one.

early social and political life

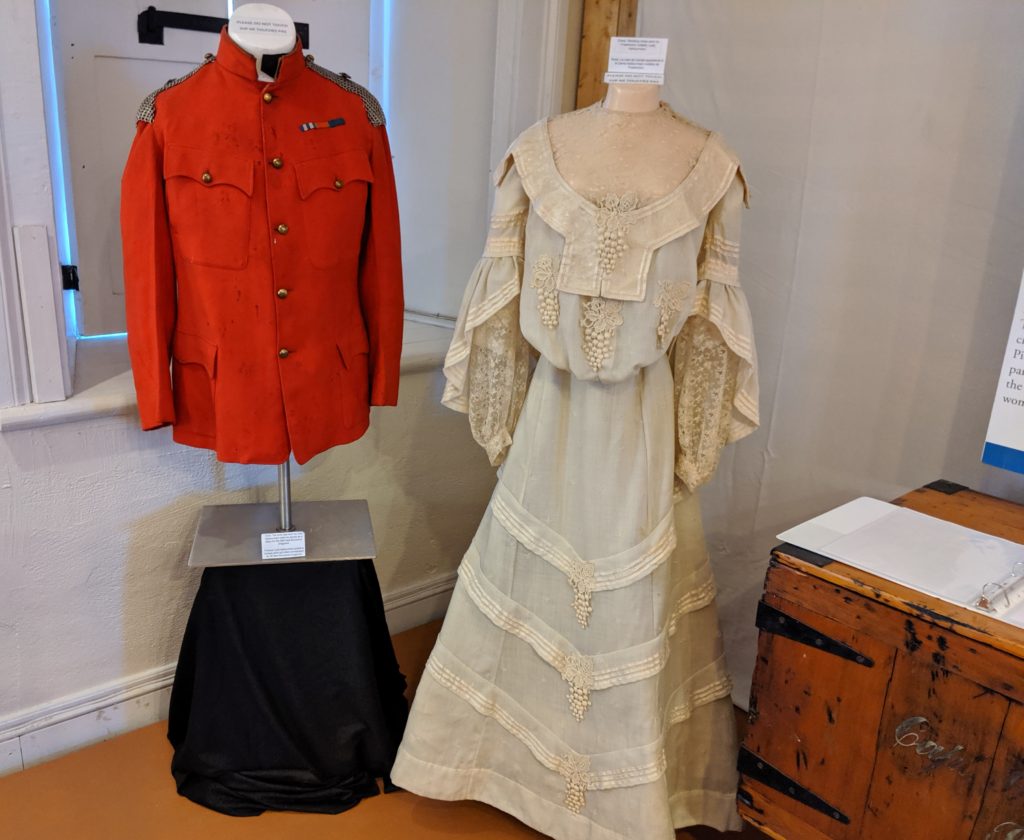

First online dating, a real love story for the ages. On military business at the turn of the 20th century, Lord Ashburnham made a call to Canada, which was received by a young telephone operator, Maria Elizabeth Anderson. The pair fell in love over the telephone and married soon after in 1903. She was a prominent woman in early Fredericton history.

One whole room was filled with the early political life here in New Brunswick, but it was rather confusing to us since it’s not our history.

The years before the confederation were unstable politically because of shifting coalitions, sectarian conflicts, and ongoing tensions between the appointed Lt. Governor and the elected assembly.

We’ll learn more about politics in New Brunswick when we visit the legislature in a future post.

transformation of medicine

Socialized medicine in Canada is well known in the states; now we get to learn how they got to this place.

At the turn of the 20th century, New Brunswick medical care was handled largely by women who treated their families and midwives who delivered most of the babies. Eventually many women sought out formal nursing training and returned to rural NB to provide “primary care” to their communities.

Practitioners known as homeopaths, osteopaths, and chiropractors found a home here. So they had trained nurses but no trained doctors.

Physicians practiced medicine by going to the homes of their patients if home medicine didn’t work. Grasping their black bag, they went out in all kinds of weather and at all hours to care for their patients. Their practice was one of travel.

These doctors “caught” the babies being born, treated serious infectious disease, and performed minor surgery including removing tonsils and drawing teeth. In 1906, the majority of registered and licensed physicians still went to the homes of their patients, but by 1950, after WW2, a centralized hospital or clinic meant physicians had patients come to them in their office hours. More people could be seen this way since the doctor wasn’t spending most of his time traveling. The era of home-based medicine was at an end.

groups of surgeries

During the 1930s, various doctors performed surgical treatments free of charge, called “bees,” especially circumcisions and tonsillectomies on groups of children. The largest of these surgeries was organized by mothers, nurses, and members of the Women’s Institute who gathered 30 children in the Dawson Recreation Hall in Marysville (we’ll be there in a future post). With 4 sets of instruments, hand suctions, cots, towels, and ice, 3 children at a time were given chloroform by a volunteer nurse. Within 30 minutes, 30 pairs of tonsils and adenoids were extracted. I wonder why so many children had to have their tonsils out?

Institutional medicine here developed rapidly after WWII, probably because of improved medical practices. Also, hospitals were seen as places of treatment and recovery rather than imprisonment or death.

Small cottage hospitals were popular in the late 19th century. Hospitals expended over the next half century. Small hospitals were built in smaller towns.

The rapid population growth in the province was driven by the dramatic growth in public service, the military, higher education, and health services—not by farming, manufacturing, or railways. The countryside of scattered rural settlements and small towns rapidly became an urban community centered around Fredericton and Oromocto. By 2001, more than 81000 people lived in greater Fredericton and nearly 2400 of them worked in the health professions.

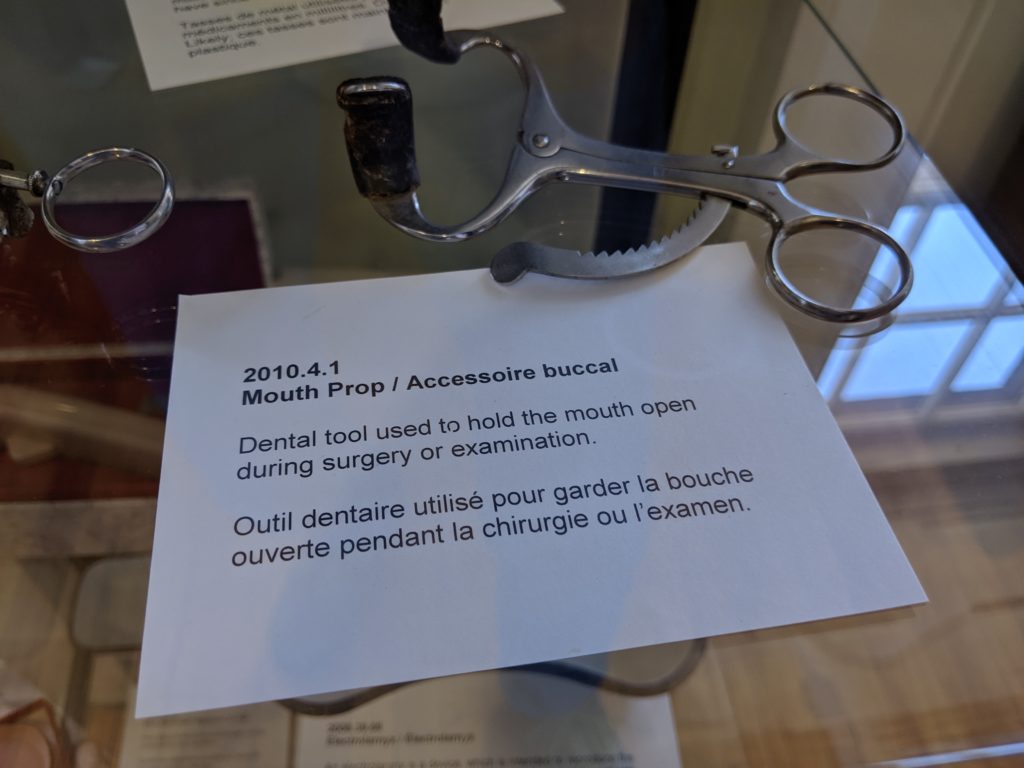

tools of the early medical trade

WWI military life

The 236th Overseas Battalion, The New Brunswick Kilties, are marching down Queen Street in Fredericton in 1916.

We know that poison gas (including chlorine, phosgene [a colorless, toxic gas with a musty odor resembling freshly cut hay or green corn], and mustard) was used in WWI on both sides beginning in early 1915. Gas was either released from cylinders to form a cloud or fired onto enemy positions using shells.

The gas curtain at the entrance of a replica of a dugout on the battlefield.

This interesting museum of NB’s history gave us a great overview. Now for a modern look at the garrison district!